This post is the summary of GTG #26 Assisted Vaginal Birth which was released in April 2020. This guideline has been update in detail with few recommendations which are different from previous version.

In this post, important points from the guideline (which could be tested in exam) are extracted. It is strongly recommended to read the original document to develop deep understanding of this guideline.

I hope this summary is helpful.

Your feedback and suggestions to improve future posts are welcome.

Your feedback and suggestions to improve future posts are welcome.

Thanks

To download the guideline : Click HereASSISTED VAGINAL BIRTH

Introduction

- Incidence of Assisted Vaginal Birth (AVB) in UK → 10-15%

- 1:3 Nulliparous deliver by vacuum or forceps

Preparation for assisted vaginal birth (AVB)

Avoiding AVB

Factors which can reduce the need

- Continuous support during labour specially when carer is not a staff member

- If not using epidural → adopt upright or lateral position in 2nd stage of labour

- With low-dose epidural→ 6% absolute ↑ in chance of spontaneous vaginal birth if lying down vs upright in 2nd stage

- Delayed pushing for 1-2 hrs recommended in nulliparous with epidural (↓ rotational/ mid pelvic AVB)

Factors which can increase the need

- Epidural analgesia although less likely with newer techniques

No effect

- Epidural either in latent phase or active phase

- Discontinuing epidural analgesia during pushing → No ↓ incidence of AVB, but ↑ woman's pain (22% vs 6%)

Insufficient evidence to recommend for reducing incidence of AVB

- Any particular regional analgesia technique

- Routine oxytocin augmentation for women with epidural

- Routine prophylactic manual rotation of fetal malposition in 2nd stage of labour

- Different studies:

- Manual rotation→ 90% success rate with ↓ in operative birth. Also ↓ duration of 2nd stage

- If corrected fetal malposition by manual rotation in early 2nd stage→ no difference in rate of AVB

- Larger RCTs are needed

Defining AVB

- Use standard classification system Table 1 and perform systematic abdominal & vaginal examination

- Marked caput→ false impression of vertex being lower than actually it is

- In deflexed occipital posterior→ fetal head may be palpable abdominally (up to 1/5th) when fetal skull at station 0 or below

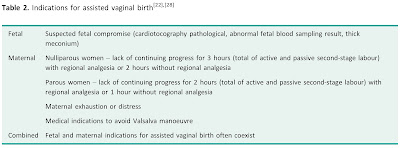

Indications for AVB

- No indication is absolute & clinical judgement required in ALL situations

- Sensible to avoid difficult AVB if ↑ chance of fetal abrasion / scalp trauma

- Forceps/vacuum→ contraindicated before full dilation of cervix

- Relative contraindications: suspected fetal bleeding disorders or predisposition to fracture

- Blood borne viral infections in mother→ not an absolute contraindication

- In preterm → higher risk of subgaleal haemorrhage & scalp trauma with vacuum than forceps

Vacuum birth

- Avoid below 32 wks -- due to risk of cephalohaematoma, intracranial haemorrhage, subgaleal haemorrhage & neonatal jaundice

- Use with caution between 32+0 - 36+0 wks

- Contraindicated with face presentation

- Not contraindicated after FBS or fetal scalp electrode application

- Avoid in suspected fetal bleeding disorders but low forceps may be acceptable

Forceps can be used

- below 32 wks

- for after coming head of breech

- in face presentation

Risks Vacuum vs Forceps (at 32+0 -36+6 wks)

- Subgaleal Haemorrhage 0.16% vs 0%

- Intracranial Haemorrhage 0.12% vs 0%

- Scalp Trauma 9.8% vs 6.3%

Deciding when to intervene

- In nullipara → significantly ↑maternal morbidity after 3 hours of 2nd stage which ↑ further after 4 hours

- No ↑ in neonatal morbidity if fetal surveillance & timely obstetric interventions used

- Consider risks/benefits of continued pushing vs AVB vs 2nd stage CS birth

- Lower threshold to intervene if several factors coexist

- Medical Indications→ cardiac disease, HTN crisis, cerebral vascular disease or malformations, myasthenia gravid & spinal cord injury

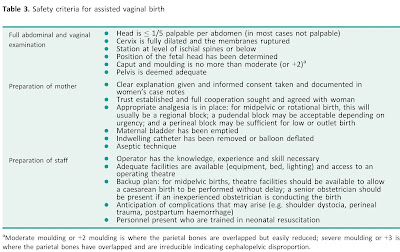

Safety of AVB (Table 3)

- Careful assessment of clinical situation, clear communication between woman and healthcare personnel

- Adequate preparation / planning is important

|

| Safety Criteria AVB |

Role of USG in assessment prior to AVB

- USG assessment for fetal head position prior to AVB

- valuable assessment tool

- more reliable than clinical examination

- operators to be trained using abdominal USG

- lower incidence of incorrect diagnosis with USG

- Correct diagnosis of fetal head position → prerequisite for safe AVB but USG in itself does not reduce morbidity

- Insufficient evidence to recommend→ routine use of abdominal/perineal USG for assessment of station, flexion & descent of fetal head in 2nd stage of labour

Type of Consent

- Birth room procedure→ Verbal (document in notes)

- Trial of AVB in operating theatre→ Written

Antenatal

- Inform women about AVB in antenatal period (esp if 1st pregnancy as high chance to have AVB)

- Take into account woman's birth plan

- Any specific restrictions/preferences → explore with experienced obstetrician in advance of labour

Labour

- Information in labour to be given between contractions

- Must document assessment findings, reasons for proceeding to AVB & verbal consent

- Mid pelvic/rotational birth→ compare pros/cons of AVB with 2nd stage CS for given circumstances & operator skill

- 2nd stage of labour--transferred to theatre

- If CS:↑maternal haemorrhage & neonatal unit admissions

- If AVB:↑pelvic floor morbidity & neonatal trauma

- Pelvic floor morbidity 3x higher at 6 wks & attenuated at 1 & 3 years

- More likely to have vaginal birth in subsequent pregnancy (80% vs 30%)

- No difference in neurodevelopment outcomes at 5 years

Performing assisted vaginal birth

Who should perform AVB?

- AVB to be performed by, or in presence of

- an operator with knowledge, skills & experience necessary to assess woman, complete the procedure & manage any arising complications

Goal of AVB: mimic spontaneous vaginal birth expediting birth with minimum maternal/neonatal morbidity

Prerequisite for skilled obstetrician: understanding anatomy of birth canal, fetal head & mechanism of normal labour

Training

Training

- Inadequate training → key contributor to adverse outcome

- Recommended to achieve expertise in spontaneous vaginal birth prior to commencing training in AVB

- If trainee performing AVB → clearly inform labouring woman that it is under direct supervision of an experienced operator

- Before unsupervised births→ competency to be demonstrated

- Competence to be assessed by OSAT form designed for AVB by RCOG

- No minimum number of supervised procedures necessary before competence is achieved (Competence variable at individual level)

- Useful to audit performance once trained

Complex AVBs: to be performed by experienced operators or under direct supervision of an experienced operator

Who should supervise AVB?

- An experienced operator, competent at mid pelvic births, to be present from outset to supervise all attempts at rotational or mid pelvic AVB

- If any uncertainty about successful AVB→ experienced operator to assess patient to ensure correct decision taken and being conducted with most appropriate instrument in most appropriate setting

- If a trainee not been assessed & signed-off as competent→ an experienced operator to be present in person for trial of AVB in theater

- No association between time of AVB (night vs day) & adverse perinatal outcome

- Senior obstetric supervision of residents → ↑ in forceps births & ↓ in CS

Where should AVB take place?

Non-rotational low-pelvic & lift out AVB

- Low probability of failure

- Most can be conducted safely in birth room

- Decision to delivery interval (DDI) of 15 minutes achievable

Higher rates of failure associated with:

- BMI >30

- Short maternal stature

- EFW >4kg or clinically big baby

- HC >95th percentile (more strongly associated with unplanned CS or AVB than birth weight)

- Occipital-Posterior (OP) position

- Mid pelvic birth or 1/5th head palpable per abdomen

AVB with higher risk of failure

- To be considered a trial

- Must be attempted in a place where immediate recourse to CS available

DDI in room vs theatre (2) studies

- operative births for all indications→ 20 min in room vs 59 min in theatre

- singleton term operative births for fetal distress →15 min in room vs 30 min in theatre

- No statistically significant difference in neonatal outcomes in either study

- No association between failed attempt at AVB & adverse neonatal outcome (except with non-reassuring fetal heart rate recording)

Instruments for AVB

- Operator to choose instrument most appropriate to clinical circumstances & their skill level

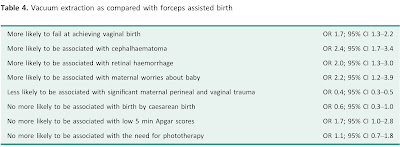

- Forceps & Vacuum extraction are associated with different benefits / risks

Vacuum

- Failure to complete birth with a single instrument → more likely with vacuum

- Soft cup vacuum extractors→ higher failure rate but lower neonatal scalp trauma

- Failure of vacuum birth

- Overall vacuum failure rate: 17-36%

- ↑3-4x with fetal malposition

- Overall failure rate with Kiwi Omincup: 13%

- Kiwi vs standard cup: 34% vs 21%

- Occipitoanterior birth vs conventional cup: 26% vs 17%

- Disposable cup vs metal vacuum: 35% vs 7%

- Kiwi Omnicup vs Bird metal cup: 2% vs 6%

- Low or outlet vacuum births:failure rate 5.8%

- Sequential use of instruments Kiwi vs standard cup: 22% vs 10%

Forceps

- Maternal perineal trauma→ more likely with forceps

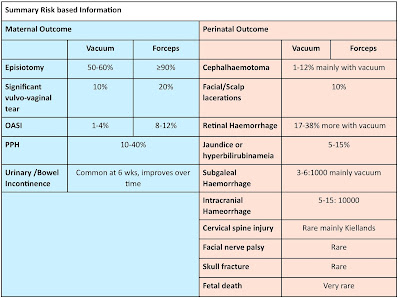

Vacuum & forceps births associated with significant maternal & perinatal complications

Maternal complications

- Higher incidence of episiotomy, pelvic floor tearing, lavator ani avulsion and obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) when compared to spontaneous vaginal birth

- Pelvic floor morbidity: includes pain, dysparunea and urinay/bowel incontinence

- Pelvic floor morbidities associated with AVB→ often as prevalent in 3rd trimester of pregnancy than postpartum

- Much of the morbidity reported by women week/months after procedure→ NOT causally related to AVB

- No significant difference in bowel or urinary dysfunction at 5 years

Perinatal Complications

- Neonatal intracranial & subgaleal Haemorrhage are life-threatening complications

- Rate of subdural or cerebral Haemorrhage

- Vacuum→ 1:860

- Forceps→ 1:664

- CS during labour→ 1:954

- Sequential instruments use (both vacuum & forceps)→ 1:256

Rotational births

- To be performed by experienced operators

- Choice of instrument depends on clinical circumstances & expertise of individual

- Options are: Kielland's rotational forceps, manual rotation followed by direct traction forceps or vacuum and rotational vacuum extraction

Kiellands forceps vs rotational vacuum birth

- Less failure/neonatal trauma with Kiellands

- Kiellands birth has 90-95% success rate & low morbidity with experienced operators

- Use of sequential instruments: less with manual rotation or direct forceps than with rotational vacuum (0.6% vs 37%). Comparable maternal and perinatal outcomes

- Complex birth transferred to theater in 2nd stage of labour: complete vaginal birth more likely with forceps than vacuum (63% vs 48%)

Discontinuation of vacuum-assisted birth and further management

Discontinue vacuum-assisted birth

- If no evidence of progressive descent with moderate traction during each pull of a correctly applied instrument by an experienced operator

Number of pulls

- Maximum of three pulls to complete birth (to bring fetal head on to perineum)

- Three additional gentle pulls can be used (to ease the head out of perineum)

- If minimal descent with first two pulls→ consider whether suboptimal application, incorrectly diagnosed fetal position or cephalopelvic disproportion(CPD)

- Less experienced operator→ STOP & seek 2nd opinion

- Experienced operator→ Re-evaluate clinical findings & either change approach or discontinue procedure

- Perform episiotomy if perineum is very resistant

- Vacuum birth to be completed within 3-4 contractions

Pop-off of instrument

- Danger of fetal vascular injury

- Discontinue→ if two 'pop-offs' of instrument

- Less experienced→ seek senior support after one 'pop-off'

- Increasing number of 'pop-offs' associated with failed AVB → OR 3.58 for 2 'pop-offs' vs no 'pop-offs'

Suboptimal instruments placement associated with

- ↑risk of neonatal trauma→ OR 4.25

- Use of sequential instruments → OR 3.99

- CS birth for failed AVB→ OR 3.81

- Low or outlet vacuum births → failure rate 5.8%

Duration of application associated with

- ↑risk of composite neonatal adverse outcomes → OR 6.9 for >12 min vs 0-2 min

Increments in Pressure

- Rapid to stepwise (0-2 kg / 2 min until 0.8 kg)→No significant difference in detachment rate, low APGAR score, scalp trauma, cephalhaemotoma & number of tractions

- Rapid increments in pressure→ significant reduction in time between applying the cup & birth with a median difference of -4.4 minutes

- Recommended to apply rapid negative pressure in vacuum-assisted birth as it reduces procedure duration with no difference in maternal/neonatal outcomes

Use of sequential instruments

- Need to balance risks of CS after failed vacuum with risks of forceps birth after failed vacuum

- Not to be attempted by inexperienced operator without direct supervision & avoid whenever possible

- ↑ risk of OASI after sequential use of instruments vs with forceps alone 17% vs 8% OR 2.1

- Judicious to use outlet or low-cavity forceps after failed vacuum to avoid potentially complex CS.

- CS in 2nd stage of labour associated with ↑ risk of major obstetric haemorrhage, prolonged hospital stay & baby admission to NNU when compared to complete AVB

- Neonatal Risks

- Must balance risk of ↑ neonatal trauma (intracranial/retinal haemorrhage, feeding difficulties) associated with sequential use of instruments

- Intracranial Haemorrhage 1:256 for 2 instruments vs 1:334 for CS after failed forceps

- Sequential use of vacuum & forceps vs forceps alone→ ↑ risk of mechanical ventilation aOR 2.22

- No ↑ in neurological morbidity up to 18 years of age in association with failed vacuum birth

Inform neonatologist team

- If failed vacuum-assisted birth +/- sequential instruments use

- Must monitor neonate for signs of traumatic injury which may not be immediately apparent at time of birth

Discontinuation of attempted forceps and further management

Discontinue if

- Forceps can not be applied easily, handle do not approximate easily or lack of progressive descent with moderate traction

- Rotation not easily achieved with gentle pressure in rotational forceps birth

Number of pulls

- Maximum of three pulls

- If minimal descent with first one or two pull→ consider whether suboptimal application, incorrectly diagnosed position or CPD

- Less experienced→ STOP & seek 2nd opinion

- Experienced→ Re-evaluate clinical findings & either change approach or discontinue procedure

Failed forceps

- Low or outlet forceps→ 5% failure rate

- Increasing number of pulls→ associated with failed AVB (OR 3.24 for ≥3pulls vs one)

- Duration of application→ ↑risk of composite neonatal adverse outcome (OR 5.37 for >12 min vs 0-2 min)

CS after failed forceps

- ↑risk of fetal head impaction at CS

- be prepared to disimpact fetal head using recognized maneuvers

- Good practice to disimpact fetal head in advance of CS birth when attempted forceps discontinued

Inform neonatologist team

- If failed attempt at forceps as ↑potential neonatal morbidity

- Monitor for signs of traumatic injury specially if multiple pulls or used >1 instrument

Role of episiotomy

- Mediolateral episiotomy

- to be discussed with woman as part of preparation for AVB

- Decision to be taken according to situation & woman's preference

- Cut should be at 60˚ angle initiated while head distending perineum

- No robust evidence to support either routine or restrictive use of episiotomy

To prevent OASI

- Stronger evidence for nulliparous & for forceps

- International studies

- Mediolateral episiotomy protective for OASI in both vacuum (9% vs 1%) and forceps (23% vs 3%)

- 5% frequency of OASI in AVB which is reduced 6-fold with use of mediolateral episiotomy

- UK studies

- Episiotomy associated with ↑incidence of PPH 28% vs 18% OR 1.72

- Risk of OASI

- ventouse without episiotomy 1.89x greater

- forceps without episiotomy 6.53x greater

Aftercare following AVB

Prophylactic Antibiotics

- Single prophylactic dose of IV Amoxicillin & Clavulanic Acid

- Recommended

- Significantly ↓ confirmed or suspected infection as compared to placebo 11% vs 19%

Thromboprophylaxis

- Reassess women after AVB for VTE risk & need for thromboprophylaxis

- Follow GTG 37a Click Here

Analgesia

- Offer regular NSAIDs (e.g. diclofenac or ibuprofen) if no contraindications

- beneficial for perineal pain

- better pain relief than paracetamol

- Paracetamol→ good safety record in postnatal & used regularly in postoperative pain

Care of bladder

- Educate woman about risk of urinary retention with AVB so they are aware of bladder emptying in postpartum

- First void urine: monitor & document the timing + volume

- Suspected urinary retention: measure post-void residual (bladder USG or catheter)

- Women having trial of AVB in theatre + Regional Analgesia:

- Keep indwelling catheter in situ (for 6-12hrs) after birth to prevent covert urinary retention

- Maintain fluid balance charts

- Remove catheter according to local protocol

- Urinary incontinence: common in late pregnancy & after birth

- Offer physiotherapy-directed strategies to ↓ risk of urinary incontinence at 3 months

Psychological Morbidity

To↓psychological morbidity after birth

- Shared design making, good communication & positive continuous support during labour/birth

- Review before discharge: indications for AVB, management of any complications & future birth advice. (Best if done by obstetrician who performed procedure)

- Offer: advice & support who had traumatic birth & wish to talk about it

- Do consider effect on partner also

- Complex association between AVB & PTSD

- AVB is one of a number of risk factors for PTSD

- Lack of control / choice for pain relief→ key associations with traumatic birth

- Women with persistent PTSD symptoms at 1 months: Refer to skilled professionals as per NICE guidance on PTSD

- The biggest predictor of emotional distress postnatally is antenatal emotional distress

- Higher rate of ≥2 PTSD-type symptoms at 3 months 7% vs 3%

- No talking to healthcare professional about their birth 42%

- No plan for further child 3 years after AVB 50% women-- mainly (50%) due to fear of child birth

- After AVB high probability of spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) in subsequent labours

- 1st pregnancy ventouse-assisted birth → 90% SVD chance in 2nd baby (although ↑relative risk but absolute risk is low)

- Complex AVB in theater→ 80% chance of SVD in next pregnancy

- Individualized future care plan: 3rd/4th degree perineal tear (specially if symptomatic) or having ongoing pelvic floor morbidity

Governance Issues

Type of documentation

- Documentation should include: detailed information on assessment, decision making / conduct of procedure, plan for postnatal case & sufficient counselling information for next pregnancies

- Use standardized pro-forma

- Process & Record paired cord blood samples following ALL attempts at AVB

- Adverse outcomes should trigger incidence report as part of effective risk management processes

Triggers for incident report

- unsuccessful Forcep/Vaccum

- birth trauma

- term baby admitted to NNU

- low APGAR (<7 @5min)

- cord arterial pH <7.10

Bulk of malpractice litigation: due to failure to discontinue procedure at appropriate time

Dealing with serious adverse events

- Ensure ongoing care of woman, baby and family

- Maternity units to provide safe /supportive framework for support of women/families and staff if serious adverse events occur

- Highly complex human factors are involved in AVB & their understanding is important

- Obstetricians have duty of candour

- Obstetricians should

- contribute to adverse event reporting, confidential enquiries

- take part in regular reviews / audits

- respond constructively to outcomes of reviews

- take necessary steps to address any problems

- carry out further retraining if needed

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete